It’s rare to find a sequel that is a complete and total improvement from the original. More often than not, I find that sequels often are weaker than their predecessors. It makes sense because for an original work to be successful enough to create demand for a sequel it has to have something special about it. But sequels often just ride on the success of their predecessors. That’s not the case with Resident Evil 2. Resident Evil 2 iterated on every aspect of the original, polishing and refining the bones of the iconic survival horror title as well as adding its own unique ideas. I encourage you to read my review of the original Resident Evil to better understand my perspective on its sequel.

Resident Evil 2 is the first game ever directed by Hideki Kamiya, who is now renowned in the industry for his work on Devil May Cry, Bayonetta, and Ōkami. Kamiya focused on the story, scraping and reworking the first drafts of the game. The main characters, Claire and Leon, end up in the zombie-infested Raccoon City. They get trapped in the sprawling police station, which owes its grandiose architecture and eclectic decoration to the fact that it was originally an art museum. The diverging paths of Claire and Leon are excellently interwoven to encourage the player to play both paths to see how they work together and how the events of the story unfold.

The writing and presentation of the story are definitely the biggest improvements from the first game. The voice acting, while still a little stilted, is so much better than the often comedic delivery in Resident Evil. Character models also got a glow-up, giving Claire and Leon more detail and fidelity. The writing in particular went from cheesy to actually thoughtful and character-driven.

While searching for her brother Claire quickly becomes an elder sister figure to Sherry, a young girl who is one of the lone survivors of the outbreak. Leon has a brief romantic relationship with the spy Ada Wong, who’s murky motivations leave you wondering if she is even on your side until the end. Even minor characters like the police chief are memorable. When you first meet him, you wonder how he survived, and something is very obviously off about him, but he gets more disturbing as you learn more about him. I wouldn’t say Resident Evil 2 is a masterpiece of storytelling, but the thriller plotlines and thoughtful characters are well-done, especially for a game of its age.

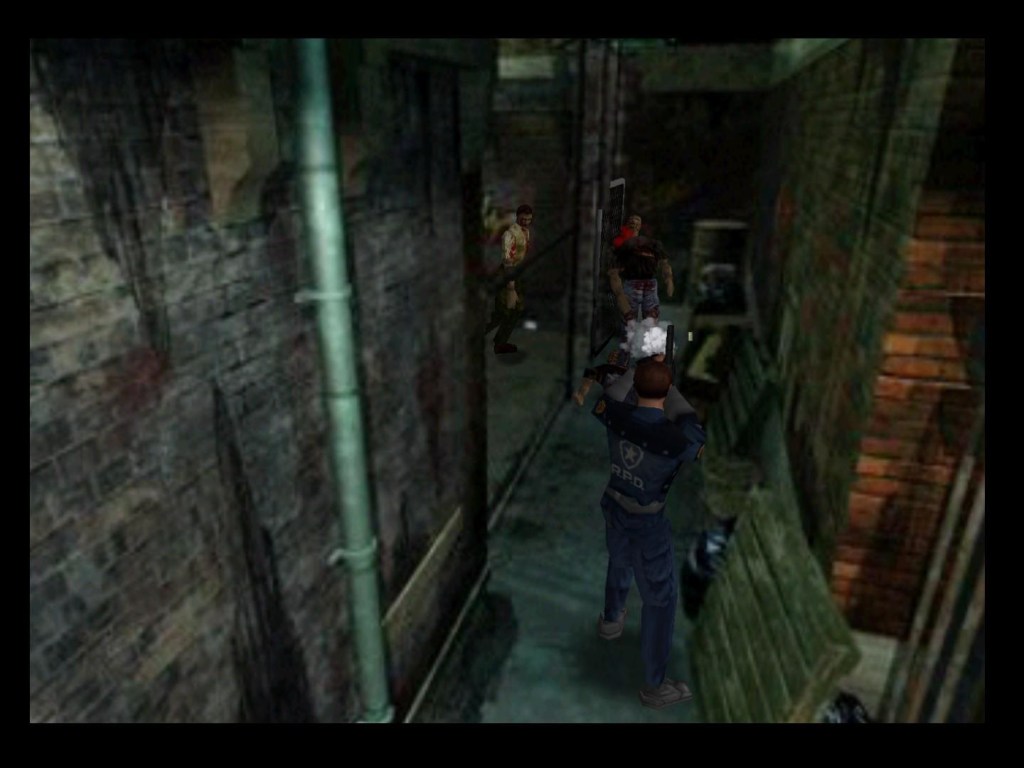

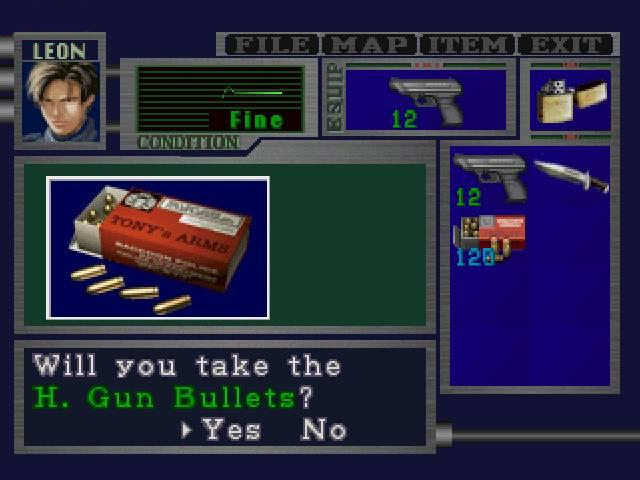

Resident Evil 2 is a survival-horror puzzle box. Like its predecessor, action takes a backseat to managing your resources and devising a strategy to escape the police station. With limited ammo, limited health-items, and limited saves, you have to think carefully about where to go next. While most enemies can be easily dispatched with the handgun, conserving ammo for the more challenging encounters is prudent. Both Claire and Leon have terrifying and monstrous entities that stalk them throughout the game, adding an additional element of tension as you never know when you’ll have to run for your life. You may think you can hold off on saving as you are only planning on going down the hall, but one of these bulky beasts could be waiting for you in a place you previously thought was safe.

The core gameplay remains largely the same from the game’s predecessor. Manage resources, solve some puzzles, navigate the zombie-filled halls of a creepy building, and occasionally shoot your way through tight spaces. While there are some new weapons, I think the most notable improvement is the diverging paths of Claire and Leon. Replaying the game is a whole new experience with new equipment, enemy placement, puzzles, and bosses. In some instances, you can even affect the world in the other character’s story. Playing both paths even unlocks the true ending and final boss fight.

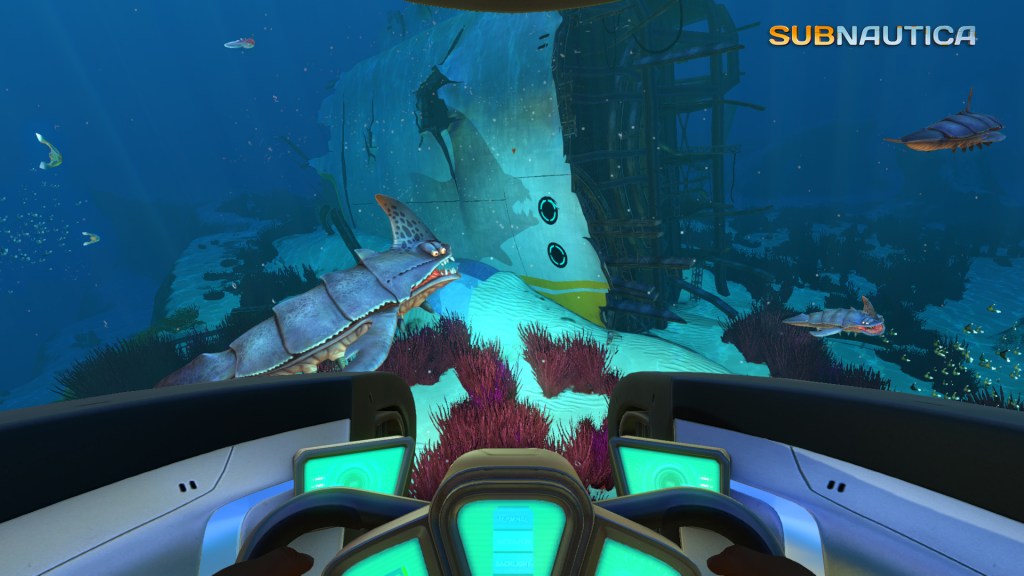

I loved the setting of Resident Evil 2. There are some brief urban sequences as you arrive in Raccoon City, running through the fires, wreckage, and hordes of zombies. There’s a sense of mayhem that is only calmed when you arrive in the police station. The police station being a repurposed art museum gives it a ton of character. From the floor layout, to the architecture, to the décor of paintings and busts, there’s a lot of charm. From there, the game descends further and further down into the grimy tunnels and secrets below the station.

My biggest problems with the game are a result of its age. Movement is still using tank-based controls, which can be supremely awkward to get used to. Especially because of the frequently-shifting camera angles. While I did get used to it after a while, more precise movement was challenging. It’s particularly frustrating when trying to run past zombies or turn during a boss fight. The dated graphics also lessens the horror and tension. The horrifying creatures just look like splotchy and blocky figures, and the fixed camera perspectives mean you rarely get surprised or snuck-up on.

Overall, Resident Evil 2 is a shining achievement in sequel development. It improved on every aspect of the original: story, characters, setting, presentation, and gameplay. The inclusion of two separate characters with their own stories and remixed gameplay was brilliant and excellently executed. While there is no doubt that the game shows its age in a couple places, once you get adjusted to the control scheme it is still a joy to play. I can’t wait to continue through the series and see how it develops from here, and I am particularly excited to revisit the recent remake of this all-time classic game.