It’s no shock to anybody that metroidvanias are an incredibly popular genre in the indie world. But a title that stands above all as a paragon of quality is Ori and the Blind Forest. Every aspect of the game is cohesive. You are the lone forest spirit Ori, and you must revive the dying wilderness which was once a vibrant habitat for all manners of creatures.

Ori and the Blind Forest is not a game with a heavy emphasis on storytelling. Aside from a couple short sequences at the start and end of the game, there is not much focus on the narrative aspects of the game. While the story does pull on the heartstrings, I think it was a great decision not to lean heavily on dialog or cutscenes. You are the last spirit of the forest, and you have to traverse a hostile environment to recover the light which sustains the forest.

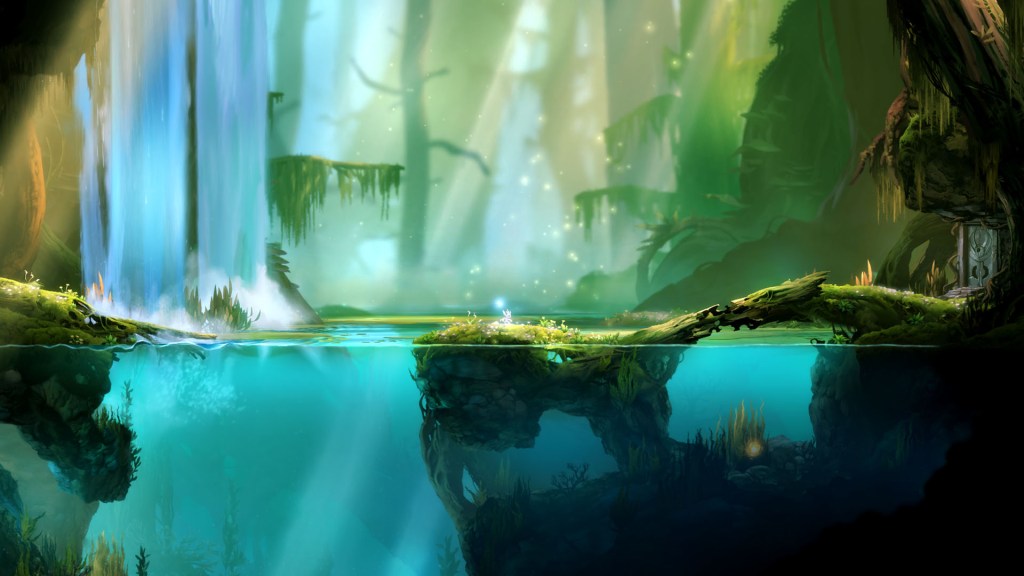

The forest is visually stunning. While many other side-scrollers opt for pixel art or other stylized techniques, Ori and the Blind Forest has gorgeously rendered environments. There is a great use of light and shadows that elicits the feeling of being in an ancient forest. There are so many beautiful effects and backgrounds that make Ori and the Blind Forest truly stand out among its contemporaries. Unfortunately, all the detailed visuals and glowing particle effects do come at a cost: visual clarity. I often times found it difficult to quickly parse the environment and decide what was a hazard, an enemy, a projectile, an experience orb, a blob of health, some energy, or any other possibility. I don’t think is a particularly brutal problem, but I often found myself mildly frustrated when what I thought was a safe spot actually damaged me.

Ori and the Blind Forest is unique among its Metroidvania contemporaries. It deemphasizes combat in favor of platforming. Combat is meant to be a last resort, and you’re much better off avoiding and slipping past enemies rather than engaging with them. Attacking is incredibly straightforward, clicking a button will unleash a flurry of low-damage light projectiles that do a little damage to enemies. There is also a charged blast attack that consumes some energy, but it often felt like a waste of a resource that could be better used elsewhere.

One of the key uses of energy is creating save points. A very unique facet of Ori and the Blind Forest is that the player is responsible for deciding where their checkpoints will exist. At any point in the game, you can spend an energy point to create a save point where you will respawn if you die. I think this is an incredibly unique idea, and it has interesting risk and reward potential. If you have a high amount of health, it may be unwise to spend a ton of energy to make frequent save points as you can afford to make some mistakes without dying. Conversely, if you are low on health, you may want to save after every little obstacle. But there is a danger in doing so.

It can be counterintuitive, but saving when you are low on health can be dangerous. I often found myself in situations where a gauntlet of challenges was on the horizon, but I had saved with a low amount of health. A single misstep could cause death. This can be frustrating because you are stuck in a difficult situation with no room for error in a game where taking damage is exceedingly common. While I appreciate the idea for a unique save system, by the end of the game I realized that I prefer the traditional checkpoints that most games have.

The main reason why I believe that a standard checkpoint system is superior to the system in Ori and the Blind Forest is that the game designers have foresight. They know when a difficult section is approaching. They know how long the gauntlet is. They know where there will be opportunities to recover health. The player knows none of this. This is problematic as it leads to guessing games of when you should expend your resources to save. If you know that a difficult section is upcoming, you may not be inclined to save with low health. If you know there’s five or six back-to-back platforming challenges, you may not want to spend your last energy point to save after the first one. Let the game designers use their knowledge to properly place and space out checkpoints for a more consistent experience.

Where Ori and the Blind Forest shines the most is in its platforming. Ori is remarkably nimble, which is cohesive with the character’s design. Interestingly, the player has very little vertical jump height, but this is made up with Ori’s long horizontal leaps and subsequent powers that are unlocked. Springing from wall to wall, climbing trees, gliding around on a leaf, and using enemies to redirect your momentum is a fantastic way to evoke the feeling of being a nimble forest nymph.

What makes the platforming in Ori and the Blind Forest really special stems from a single ability: Bash. This skill is gained relatively early on in the campaign, and it makes the gameplay far more dynamic. Bash allows the player to launch themselves off of enemies and projectiles, knocking them in the opposite direction. You can swiftly rocket through corridors using a mixture of regular platforming and Bash to dodge and use enemies to your advantage. Its this single ability that makes up for the lack of combat, as Bash begs the player to just dash through enemies and launch them into hazards rather than engage with them. It makes sense then why the developers opted to omit traditional boss fights in favor of epic escape sequences. These are adrenaline pumping sections that demand speed and mastery of your abilities, and I love the decision to include them.

As for its metroidvania aspects, I found Ori and the Blind Forest to be passable. There was a rapid pace of unlocking new traversal abilities to reveal new paths. While there wasn’t a ton of necessary backtracking or revisiting prior areas, there were plenty of secrets to be uncovered. Unfortunately, most of the secrets were somewhat uninteresting as they were mostly additional experience or health/mana upgrades. Even though there was a lack of backtracking ala Metroid, Ori and the Blind Forest scratched the exploration itch as it certainly was not linear. There were many branching paths and routes to traverse, making for some satisfying exploration.

It had been a long while since I originally played Ori and the Blind Forest, and I am so glad that I revisited it. There are so many unique ideas here such as the emphasis on platforming, the focus on horizontal movement, the save system, and the use of escape sequences in lieu of bosses. Despite its faults and missteps, Ori and the Blind Forest is a phenomenal metroidvania. There is good reason why even modern indie games are compared to Ori and the Blind Forest, even if few meet the high bar that it set.