Gwent is one of the best “game within a game” examples ever. In The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt, the player can take a break from monster slaying to sit down and play the card game known as Gwent. I probably spent more time in taverns playing this addicting minigame than I spent actually adventuring. I was elated to hear that there was a fully-fledged roleplaying game that utilized Gwent as its main mechanic. Yet my actual experience with Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales was more of a rollercoaster than the fun revisit to Gwent that I was expecting.

My first moment of confusion was during the tutorial, when I realized that this version of Gwent was monumentally different than what I played in The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt. In the original version of Gwent, each game would have three rounds, and the player to win two rounds won the match. The interesting facet was that you only had ten cards for the entirety of the match. You may win a round, but if you played too many cards doing it, you were in a poor position to win the match. It was interesting as the players had to come up with powerful combos that only required a few cards, or use cards that allowed them to gain tempo on their opponent. You had to know which round to intentionally lose and how to bait your opponent to playing their good cards too early. It was a game of strategy and momentum.

The Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales version of Gwent is substantially different for the most part. Most battles do not even retain the standard 3-round format. The majority of matches in this game are single round affairs, which to me is missing such a crucial aspect of the original game. When the game is only a single round, it just becomes an arms race of who can play the most powerful cards and combos. Previously, you had to play your powerful cards at optimal times such that you wouldn’t waste them on an already won round, now it doesn’t matter.

Truthfully, the original version of Gwent had its own fair share of balance problems, but I would’ve liked to see the design team work on fixing those problems rather than just changing the entire format. The three round battles do still exist, but they aren’t plentiful. Eventually, the new version of Gwent did grow on me, but it was incredibly off-putting the first time I played Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales. The original version needed changes to rebalance it and keep it fresh, but it didn’t need an entire overhaul.

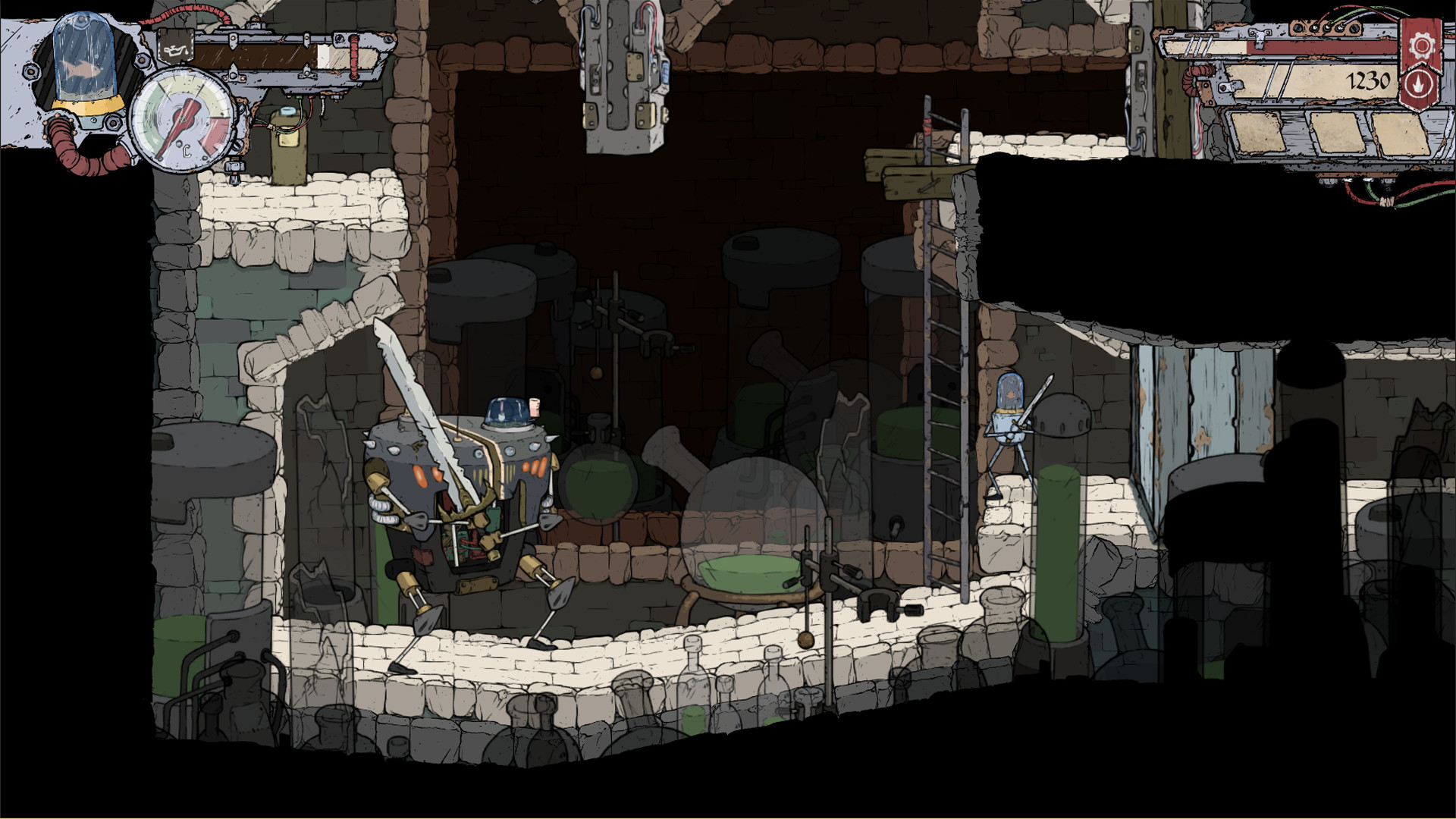

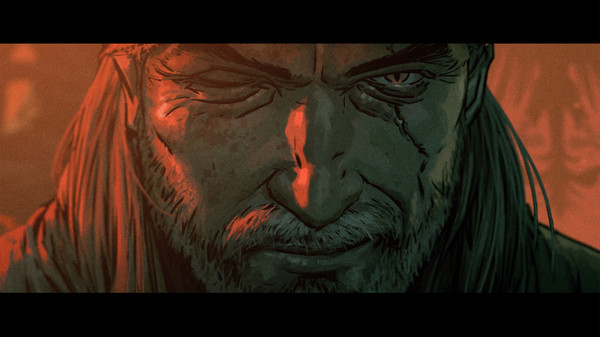

Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales follows the story of Queen Meve and her campaign against Nilfgaardian invaders. This war precedes the events in the mainline trilogy of The Witcher. You play as Queen Meve, the ruler of Lyria and Rivia, during an invasion of her homeland. The warrior queen is conspired against and forced from her throne, and the game follows her adventure to rebuild her army and retake her kingdoms. In typical fashion of the series, there is an abundance of decisions to make, often with no obvious answer. The game plays as a top-down point-and-click adventure game, and the battles are represented by the card game Gwent. As you travel across the various areas you will have to make many moral and strategic decisions regarding your army and subjects.

The presentation of the game is top notch. The artwork, voice acting, story, and interactions with the various characters in the game was the absolute highpoint of the experience. The story itself was fairly intriguing, but the characters and decision making carried the game. You meet various important figures throughout the game who you can recruit to advise Queen Meve and join her army. But every decision has potential for backfiring completely. You may want to recruit an elf who was being attacked by humans, but maybe that elf is a spy and will betray you and sabotage your army.

Each decision not only has ramifications not only in the story, but in regards to your army as well. Recruiting new characters lets you use their special card during battles. But be careful, as a bad decision may lead to you losing resources like gold or soldiers. The universe of The Witcher is a tumultuous one, there are many factions vying for power. Subterfuge is a common tactic to weaken opposing forces. Be aware that whoever you decide to recruit and rely on may at some point betray you.

As previously mentioned, the core “action” in the game is represented through the card game Gwent. You can modify your army by swapping out cards and building a deck that fits your needs. To craft or upgrade cards, you gather three resources as you explore: gold, recruits, and wood. You use these resources to supply the war machine, which of course is represented by your deck of cards. The deck building aspect of the game is pretty fun, as cards have various effects that you can find synergy between. There are many different strategies that can be played around with. You can make a deck that spams the board with tons of cards, or focus on just powering up a few specific cards, or you can use cards that deal damage to your opponent’s cards. There are a lot of different options to try out, and the game is not shy about introducing new sets of cards to experiment with.

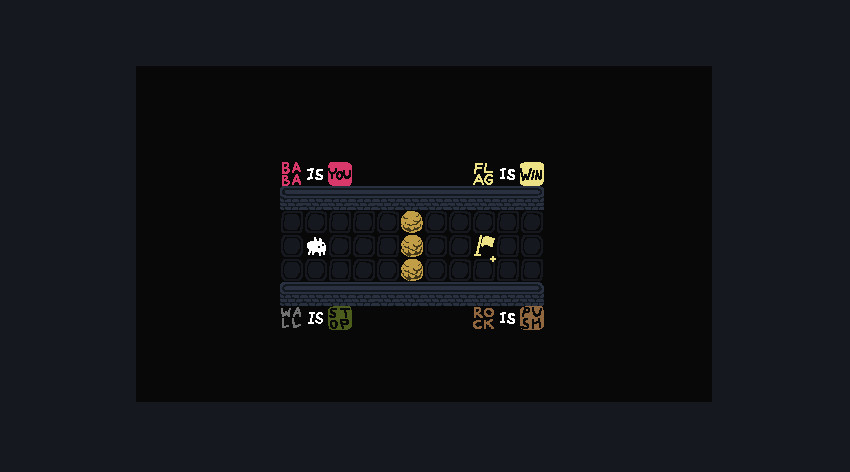

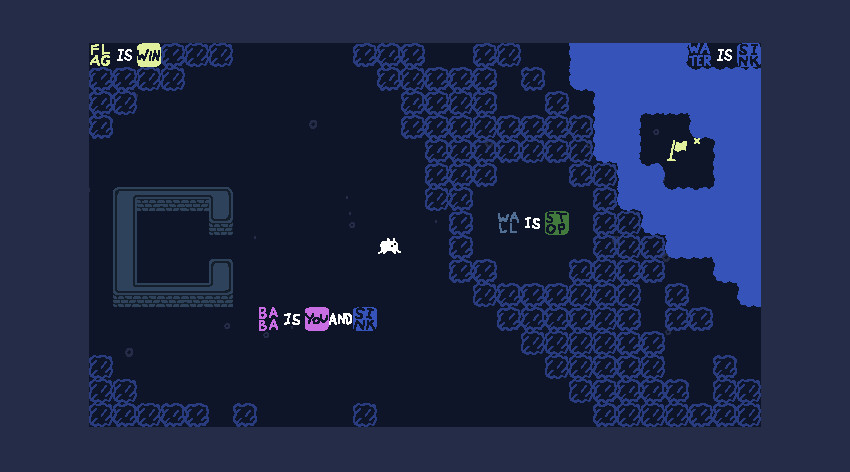

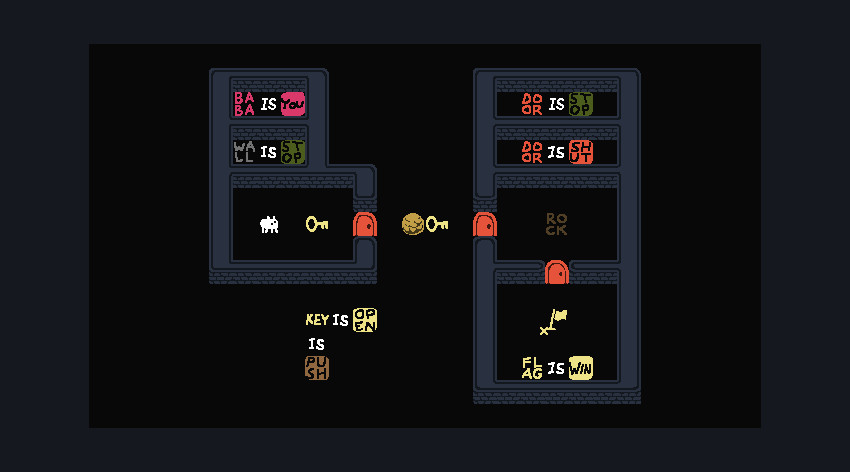

Despite feeling a bit frustrated at the differences between the original Gwent and this new version, the card game variation of Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales eventually did grow on me. The cards in this game are much more complex than its predecessor. Each card has a unique effect, which you can often chain together for some synergistic combos. Finding out which cards worked well together was a lot of fun. Perhaps the most interesting encounters were the frequent “puzzle battles”. In these battles the player is given a preset hand and a special objective. Usually there would be a specific order of operations in how to play the hand to complete the battle. These were nice detours from all of the standard Gwent encounters, as those could grow repetitive very quickly.

Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales is a fairly long game; it takes about 30-35 hours to complete. For the amount of content in the game, that is too long. Gwent can be a lot of fun, and I was invested in the story and characters, yet I was burnt out entirely by the time I reached the end of the game. I think the problem stems from the fact that once you build a sufficiently powerful deck, you can just steamroll every single encounter the same exact way. By the second or third chapter in the game I had created a deck that easily dealt with nearly every battle, and I didn’t really have to think much outside of the more unique puzzle battles. This led to many of the encounters feeling very same-y and repetitive. This was exacerbated by the fact that the 4th and 5th chapters of the game are filled to the brim with repetitive battles that have absolutely no impact or relationship to the story.

The repetitive nature of the game could have been at least somewhat avoided if the game encouraged the player to craft multiple decks or to at least switch it up from time to time. While you do unlock plenty of cards during a playthrough, you still need to use resources to craft them. This disincentivizes the player from trying out new decks unless they absolutely need to. If you have a deck that works well, there’s no need to waste resources that you may need later. The odd thing is that the game forces the player to switch up their deck in the transition from chapter one to chapter 2, then never does this again. I understand not wanting to force players to stop using decks that they may enjoy using, but they could have at least encouraged rebuilding your deck from time to time.

My last complaint with the game may be a petty one, but I absolutely despise the design of the final boss. I played on the highest difficulty available, and for the most part the game was never too challenging. But the final boss was an absolutely insane difficulty spike that felt blatantly unfair. He has multiple abilities that are individually so overpowered that just having one would be plenty challenging.

His first ability makes it so any card that you destroy will automatically be replaced by a card in his deck, so it becomes detrimental to destroy any of his cards. His next ability allows one of his cards to get a 10-point strength boost every turn, which is a fairly large amount. For reference, one of Queen Meve’s possible abilities boosts a card by only 4 points, and it has a 4-turn cooldown. Finally, he has numerous cards that are so absurd they feel like a joke. One in particular allows him to draw 3 extra cards and also boosts every one of his cards by 2 points. In a game where you can’t draw cards outside of special circumstance, having a card that allows you to draw just one extra card would be valuable, let alone three extras and a power boost to go along with in.

I pretty much steamrolled the entirety of Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales up until this final encounter. In fact, this was initially an unwinnable encounter for me. My deck was tailored to do damage and destroy enemy cards. Yet this tactic is literally unusable against the final boss, since destroying his cards just causes another to spawn in its place. I had to scrap my entire deck and rebuild it from scratch specifically designed to beat this one encounter. Even then it took me numerous tries to finally be successful. It just is not a fair fight under any circumstance.

Overall, my experience with Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales was all over the place. I initially was not happy with the changes to the key formula of Gwent. It eventually grew on me and I had a lot of fun for a few chapters. The worldbuilding, art, story, decision making, and characters were all top-notch. Then the prolonged ending and absolutely aggravating final boss left a poor taste in my mouth. It is for these reasons that I give Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales a 6.5/10. This is a game that could have benefitted from cutting out a bunch of superfluous content and focused on just the key battles instead.