Growing up I loved Pikmin. I never beat the game until I was older, but I loved playing it nonetheless. Real-time strategy (RTS) games can be intimidating as they have steep learning curves and can brutally punish the player for mistakes. But not Pikmin. This is an approachable RTS, so much so that it’s accessible for children. Yet there were plenty of bold design decisions that shaped how Pikmin is played, and I think those risky choices ultimately are what make the game so fantastic.

You play as Captain Olimar, a funky little spaceman who crash landed on an alien planet. He only has 30 days of life support to sustain himself and you need to recover 30 missing spaceship components. Captain Olimar discovers a creature that he dubs Pikmin and he learns how to command and lead them so he can fix his ship and return home. It’s a simple premise, but there’s a few key aspects to take note of.

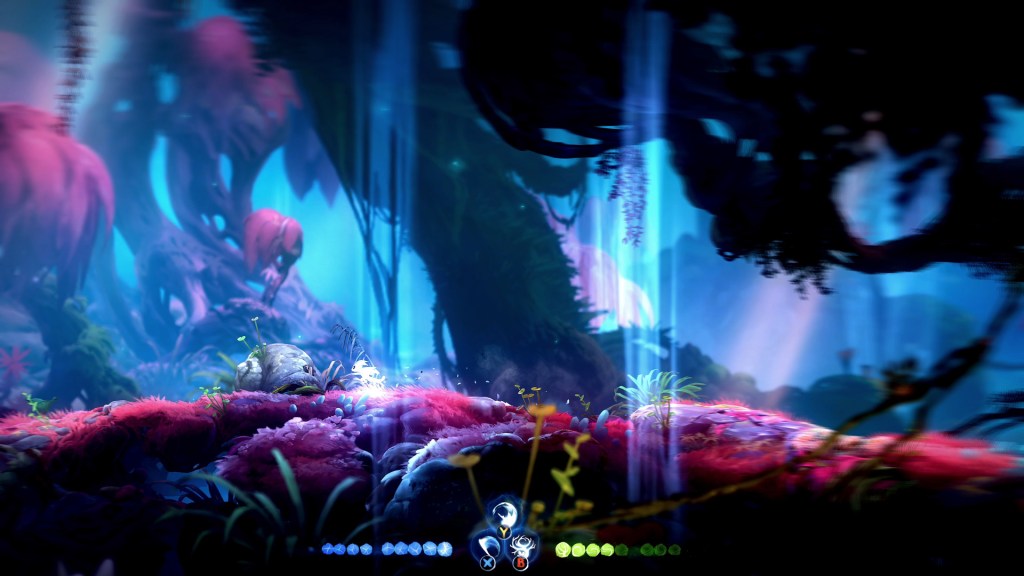

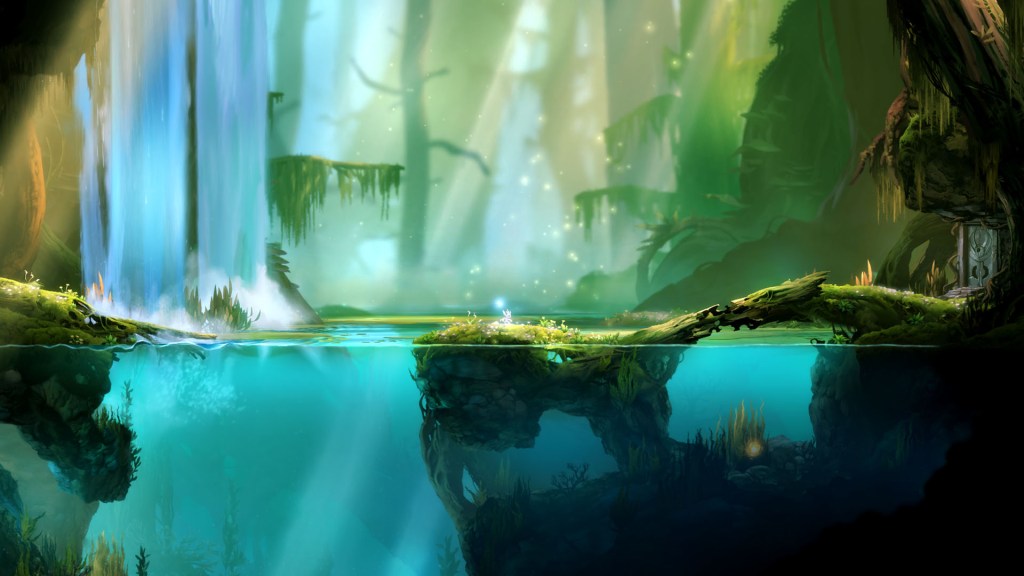

One of the first things that any player will notice about Pikmin is its setting. While Captain Olimar says he has landed on an alien planet, you’ll realize that the planet is only alien to him. The foliage and environmental design of Pikmin is obviously Earth from a microscopic perspective. Grass, stumps, and flowers tower over the player. Empty bottles and cardboard boxes are common obstacles. Most of the threatening fauna seem like evolved versions of common worms, flies, and ladybugs. I love this setting because it is immediately recognizable, but it does feel remarkably alien. Being scaled down makes the world feel monumentally different, and you have to learn how to survive.

A key component to survival in this alien setting is learning how to utilize Pikmin. The game frames this excellently to compliment the context of learning how to persevere in an unfamiliar environment. There are three types of Pikmin, each with their own properties and niches to understand. The world is rife with hazards such as fire, water, and of course various enemies. I love how Captain Olimar makes observations like how the Pikmin respond to the whistle, or that the blue Pikmin have gills and may be able to swim. While it seems tempting to just bring a bunch of each type of Pikmin everywhere you go for every situation, that can be a risky proposition.

I love how many subtle decisions go into playing Pikmin. You can have 100 Pikmin in your legion at any time, but controlling a big group can be massively unwieldy. It’s easy for them to get caught going through corridors, get picked off by roaming enemies, or accidentally fall into a pit of water. There’s a sort of parental instinct that kicks in when you play Pikmin, they are cute little guys who you planted and raised, there’s no way you want to risk a single death if you can help it. I often only explored with smaller groups of Pikmin so that I could always account for each and every one of them.

While the primary objective of the game is to recover ship parts, there’s a lot of preparatory work to achieve that goal. Walls need to be knocked down, bridges need to be built, you need to build up a force of Pikmin, you need to feed nectar to your Pikmin to empower them, and enemies need to be cleared out of the way. The game is a constant juggling act of small objectives, and it’s easy to feel accomplished with how quickly you progress.

Part of what fuels the rapid decision making of Pikmin is its most risky aspect: the time limit. It’s intimidating at first. 30 days to recover 30 parts. 1 part per day. And each day is only 13 minutes long. Truthfully, it’s a pretty generous limit. It’s often feasible to recover multiple parts every day, or at least make progress towards the next one. Nevertheless, the pressure of a time limit fuels the player to work quickly and attempt to multitask and make risky decisions. You can leave Pikmin to their own devices to take down walls or carry things back to base, but they are extremely vulnerable to predators. Moreover, any Pikmin left alone at the end of the day will be eaten. But if you want to get multiple parts in a day, you have to take that risk.

Time limits can often be off-putting by putting pressure on the player. But the time-crunch serves Pikmin well. You have to make decisions on the fly about what to do with your limited time. Whether it be planting new Pikmin, knocking down walls to serve as shortcuts, or just defeating enemies so they aren’t an issue for a few days, there’s always something to do. The time limit provides real tension and a sense of stake. But it isn’t oppressive as there’s an abundance of time to fully restore Olimar’s ship.

If I had to complain about something about Pikmin, itis the artificial intelligence for the Pikmin themselves. I think it’s ok that they’re kind of dumb, as it contextually makes sense. They have a symbiotic relationship with Captain Olimar. They can use their overwhelming numbers to assist him, and he can use his brain to tell them what to do and help them reproduce. But at times they are just a little too dumb. Enough to be frustrating. It’s a pain to wrangle suicidal Pikmin who got distracted by grass or nectar. Or when throwing them at enemies to engage in combat I often found that the Pikmin would prioritize picking stuff up to carry home rather than attacking. I think it’s fine that they have a one-track mind, but when they actively ignore the player’s direction it can be frustrating.

Ultimately, Pikmin expertly marries its gameplay and narrative. From the somewhat-familiar alien setting, to the learning process of commanding Pikmin, to the parental responsibility that you feel for the titular creatures, to the impending doom that the time limit imparts, the game really does put the player in the shoes of Captain Olimar. And it does all this while remaining fun and accessible for all audiences. Pikmin has always been overlooked compared to other Nintendo juggernauts such as Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda, but in my opinion it’s just as classic.