As a lover of tactical RPGs, I am upset that I let Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle sit on my shelf for nearly 7 years. While the game seems like a bizarre concept, it is an incredibly well-made game. It innovates on common systems such as hit rates, movement, and special abilities to make for a surprisingly deep tactical experience. While playing it safe is often the key to success in other tactics games, Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle encourages aggression and fast-paced play. And while I still think the concept is odd, it somehow works.

When this game was announced as a mash-up of Mario and Rabbids in which they would use guns in turn-based tactics battles, I thought there was no way it would be good. It felt like 3 diametrically opposed things being merged into some bizarro concoction. But it actually works. Mario and his pals team up with a handful of Rabbids cosplaying as Mario characters to take down the out-of-control virus that is corrupting everything.

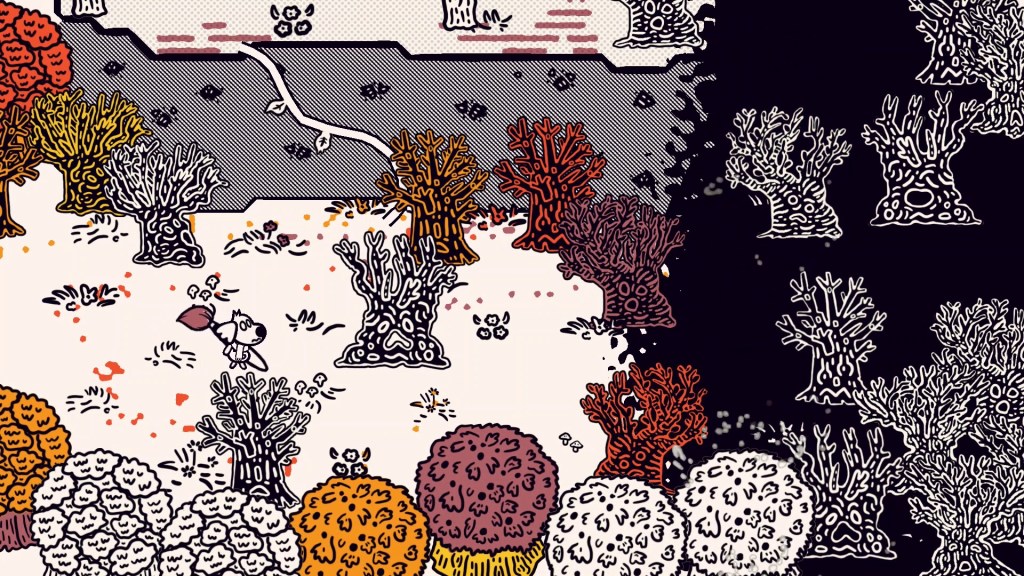

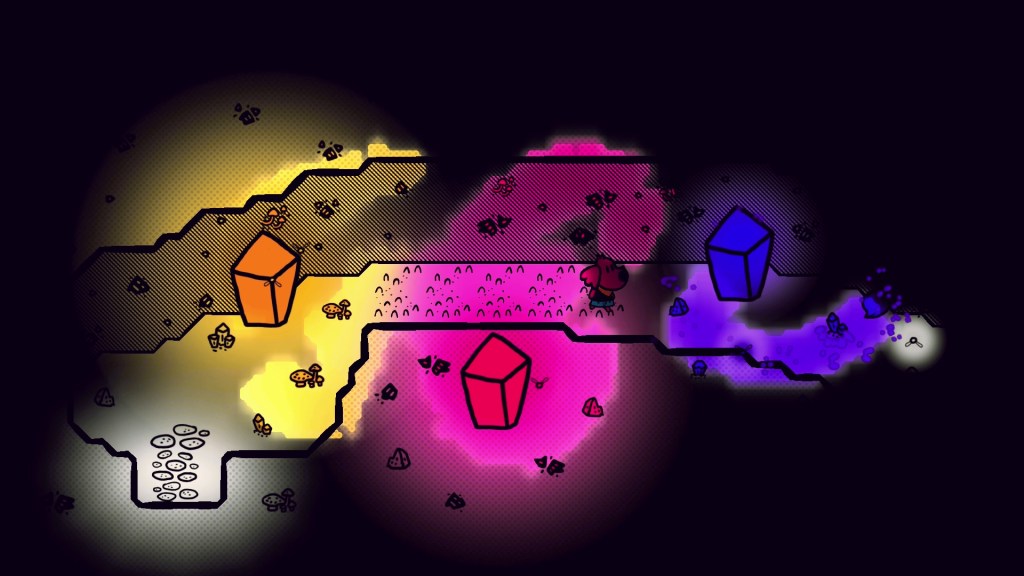

The Mushroom Kingdom, as always, is a fun backdrop for the adventure. It’s bright, colorful, and has a set of classic areas to explore. Walking around the world only serves as a breather between battles, but I enjoyed soaking in all the wacky details. The invasion of Rabbids has left the Mushroom Kingdom and its denizens in chaos. And the Rabbids are strewn about, causing mayhem with their signature brand of physical comedy. Luckily, I think the Rabbids were toned down a bit in terms of their obnoxiousness. They are infamous for how annoying their schtick can be, so I’m glad that it was reduced to more reasonable levels.

Aside from the concept, Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle surprised me in how many smart ideas it had. One of the biggest examples of this is the 0/50/100% hit rate system. In most other tactical RPGs, whenever an attack is initiated, there is a complex formula to calculate the odds of the attack landing. This is a core mechanic to games like XCOM in which the player tries to optimize their odds of success while staying in a safe position to minimize enemy hit rates. But the issue I’ve always had with XCOM is how outrageously bad it feels to carefully enact a strategy that relies on a 97% shot, but it fails and you are severely punished. It’s just how odds work, but that doesn’t stop it from feeling terrible.

In order to combat this feeling of getting unlucky, Fire Emblem implements its own system. It amplifies the percentages under the hood, so a high percentage like 90% is really closer to 98%, while a low percentage like 20% is more like 8%. While it is directly lying to the player about odds, I think it works wonderfully because the player shouldn’t be basing their strategies on low percentage attacks. It just makes the game feel better and doesn’t make you feel like you got unlucky as people are notoriously bad at estimating odds. Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle gets around this conundrum entirely by boiling down hit rates to 3 categories: 0%, 50%, and 100%. If attacking an enemy fully behind covered, you will not hit them. If they are partially behind cover, you have a 50/50 shot. And if they are in the open or you flank them, you a guaranteed to land a hit.

I think this system is genius because of how simple it is. You are encouraged to flank enemies, as you can’t reliably hit them otherwise. There’s no frustration in missing a high-percentage attack because they simply don’t exist. You almost always know beforehand whether the attack will hit, and hitting 50/50s should be seen as a bonus, not a core part of your strategy. You can’t blame luck when you miss a coin flip. There are other forms of statistics in the game, like weapons that have a range of damage they can inflict and can occasionally trigger special effects. But like with the 50/50 shots, you shouldn’t rely on special effects or max damage attacks as they are uncommon. If playing well, you always know when an attack will hit and the base amount of damage it will do, anything on top of that is a bonus. This simplified hit system is such an intelligent mitigation technique of the player feeling unlucky when playing tactical games.

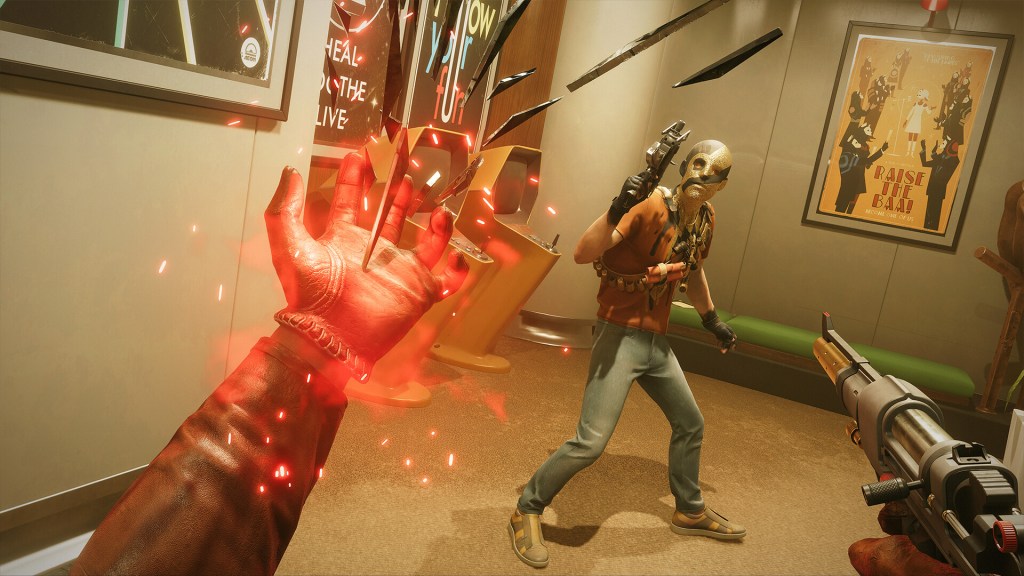

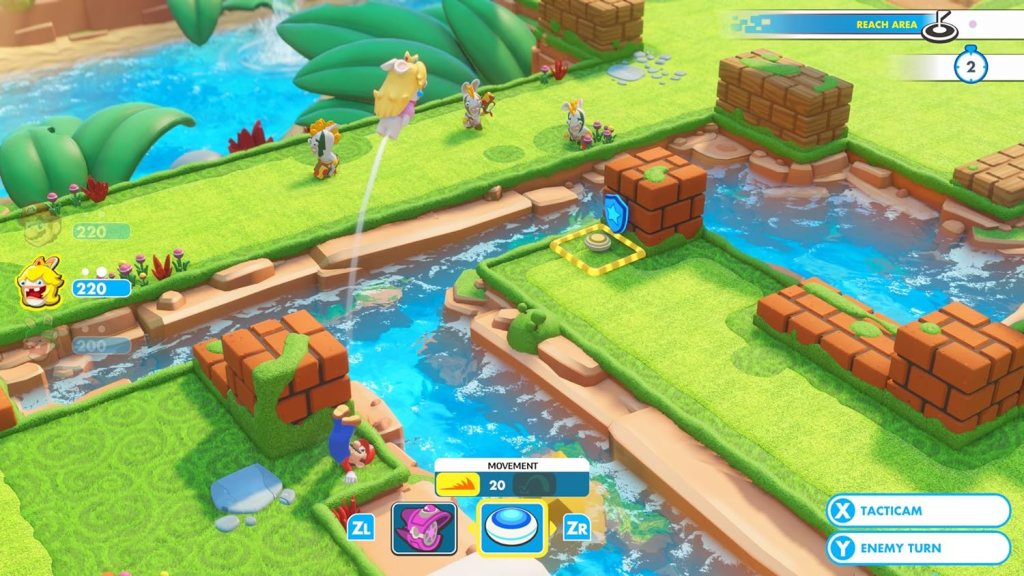

Even though the hit system is simplified, Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle has a surprising amount of depth. The battles are small, you only can control 3 characters in relatively compact maps against a handful of foes. But each turn brings so many possibilities that it’s staggering. Each character has two weapons, two special abilities, and some extreme mobility. On a single turn for a single character, you will be able to move, dash through an enemy or two to deal damage, jump off a teammate for extended movement, attack an enemy with your weapon of choice (which also have a reasonable chance to trigger special effects), and decide if you want to use a special ability. And you can take these actions in any order you want. The breadth of options here is immense.

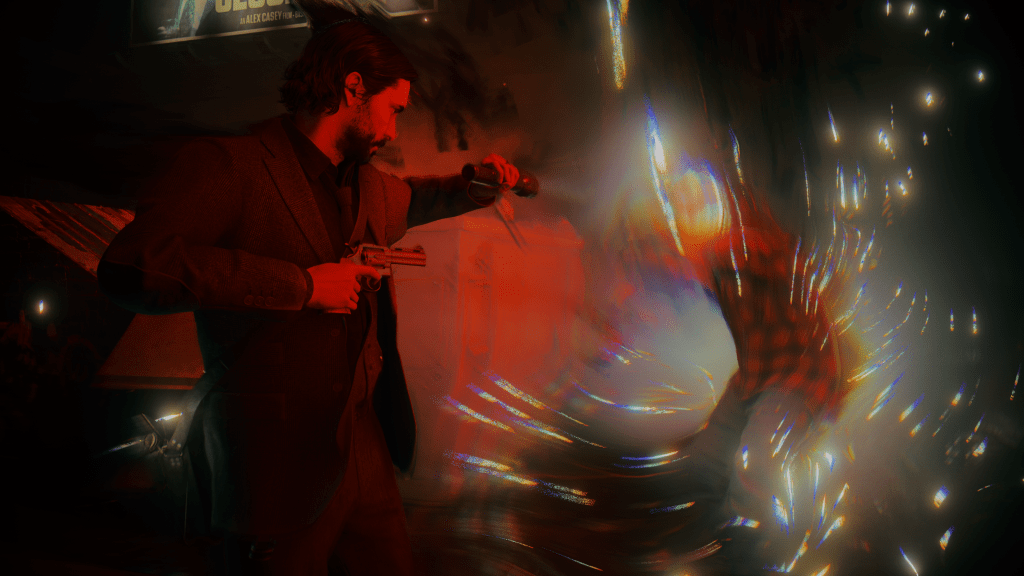

All of the possibilities available to both the player and the opposition make for some extremely dynamic battles. The extreme mobility and combat capabilities paired with destructible environments make it difficult to predict exactly how any given turn will play out. This encourages aggressive play. You should maximize your own capabilities to take out as many enemies as possible before they get the chance to retaliate. Every turn feels like a mini-puzzle as to how to get the most out of your character’s actions. Moreover, if you want to get a “perfect” score on every stage then you have to complete the battle in a set number of turns, further encouraging you to play aggressively. I love that flanking and going on the offensive is the best strategy, as many other tactical games encourage turtling and playing overly safe.

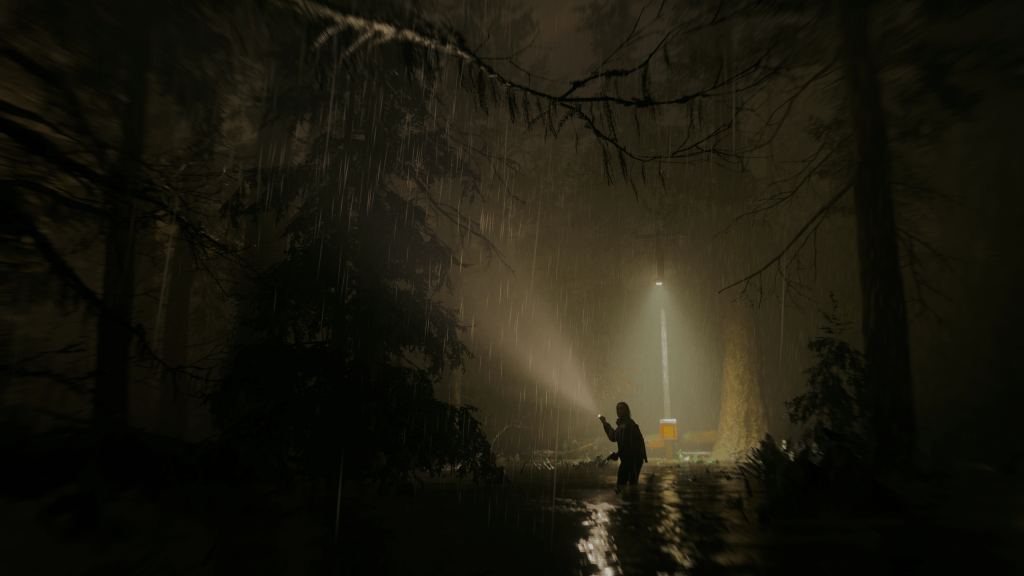

Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle can actually be pretty tricky at times. Enemies can easily flank and position themselves to deal massive damage. Boss fights are multi-staged affairs with unique mechanics. And there’s tons of enemy variety sporting different weapons and effects to watch out for. This makes for some fun challenges as you learn how to utilize your characters effectively. The upgrade system encourages you to specialize your characters to bring out their strengths.

My only complaint about the gameplay is that I wish it encouraged more experimentation with party members. You can only have 3 in any given battle, and 1 of those is required to be Mario, leaving only 2 options for other members. All the characters were unique and had some interesting abilities to be utilized, but I never really strayed from my core party because I didn’t need to. My setup of Mario, Luigi, and Rabbid Luigi was more than capable of taking on any of the main campaign and all of the bonus levels. Maybe if the game didn’t have such restrictive limitations on my party, I would’ve tried different characters. Another option is if there were challenges that encouraged the use of members that you haven’t utilized that showcased each character’s niche.

Aside from gameplay, I did have a handful of minor gripes about the user interface and user experience. The camera during battle left a lot to be desired. I wish you could freely rotate it and zoom out to see the entire battlefield. It wasn’t a huge deal as most maps are tiny, but some of the missions are massive and it can be difficult to grasp which route to take to the goal. Another improvement that I would’ve liked to see is the ability to toggle enemy movement and attack ranges. You can do this for a single enemy in a special menu, but there’s no way to leave it on for when you are actually making a move. You just have to memorize their range if you are trying to keep a character out of harm’s way.

The biggest issue I had with the user experience is just how long everything takes. There’s a panning camera shot at the beginning of the battle, a celebratory animation when you win, and a ton of seemingly random cinematic animations that occur during battle. These cinematic animations can happen anytime, whether you are just sliding for a little bit of damage, attacking normally, or triggering an ability. They do look nice, but this is a fairly lengthy game with a ton of battles. You are going to be seeing the same animations over and over and over. The battles themselves are only a few turns long, but they can take a while simply because there are so many actions and superfluous animations. You can speed up enemy turns which is a great feature, but I would’ve liked options to be able to speed up all animations and disable the cinematic animations altogether.

Overall, I was shocked how much I enjoyed Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle. I thought the game would be too simplistic to be engaging, but I was proved completely wrong. Every turn has so many dynamic possibilities that lends to aggressive play. The 0/50/100 hit percentage system was a genius method of alleviating frustration and encouraging flanking maneuvers. Despite a few little UI hiccups, Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle is a phenomenal strategy game. If you are like me and have Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle sitting on your shelf, do yourself a favor and give it a try.